Commentary Legend Clive Everton Passes Away

Clive Everton, one of snooker’s greatest ever commentators and voice of the sport, has died at the age of 87.

Everton devoted his life to snooker and covered the some of the sport’s most historic moments as a broadcaster and journalist.

Commentator David Hendon was a protege of Everton and a close friend. Here is his obituary for a snooker legend.

Clive Everton deserves to be remembered as one of the most significant figures in snooker history.

He reached a highest world ranking of 47th but it was off the table where he made a vast and varied contribution, primarily as a broadcaster and journalist but also as the trusted conscience of the sport.

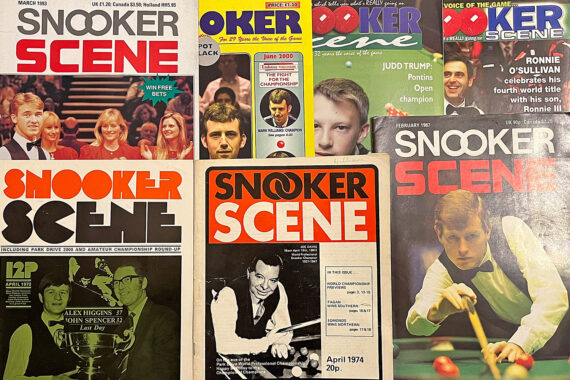

As editor of Snooker Scene for 51 years he provided an invaluable chronicle of snooker’s rise from folk sport to a mainstream television attraction, charting the careers of players from boyhood to stardom. He forensically examined the governance of the professional game and campaigned for change and transparency.

Clive was also passionate about billiards, the game in which he particularly excelled, and he worked tirelessly to promote it and help it survive.

In his book, Black Farce and Cue Ball Wizards, Clive explained how this love affair began:

“My emotional commitment to the game dated back to boyhood and one rainy London afternoon when my father and I settled into the plush fauteuils of Leicester Square Hall, which was then the 220-seat home of the professional game. From the first click of the balls, I was entranced.”

Clive won the 1952 British under 16 billiards title but the reputation of cue sports was such that his achievement received little recognition.

He wrote: “Far from making me any kind of hero at school – King’s, Worcester – this success made me more of an outsider and nurtured, in turn, my anti-establishment instincts. My headmaster, F. R. Kittermaster, an Old Rugbeian from the Thomas Arnold tradition, wrote in Sport and Society that only sports with an element of physical danger like rugby, cricket or hockey, were ‘character building.’ He was fond of insisting: ‘You came here to be made into gentlemen.’ Proficiency at billiards, the classic sign of a misspent youth, did not fit into his definition.”

This did not deter Clive, whose attitude to authority was always one of scepticism. He went on to win the British under 19 billiards championship and at age 22 the first of four Welsh amateur billiards titles. He reached the final of the English amateur championship on five occasions.

He was also talented at tennis, competing for the Worcestershire county team and entering qualifying for Wimbledon.

A BA Hons English graduate of Cardiff University, he moved to the Midlands after marrying Valerie, whose father arranged a teaching job at a college of further education in Halesowen. Clive taught English and Liberal Studies but journalism was what he wanted to do.

He was helped by Rex Williams, with whom he would practise and who negotiated columns in the Wolverhampton Express and Star and its sporting ‘pink’ published on Saturdays.

Clive also picked up some freelance work as a tennis and hockey writer and after a year in post gave up his teaching job to pursue journalism: “What it amounted to was that I loved sport and wanted to spend my life in it.”

Enterprising and ambitious, Clive was determined to succeed but also to push the cause of snooker and billiards. In 1966, he was appointed editor of Billiards and Snooker, the magazine of the Billiard Association and Control Council. Still a young man and an independent thinker, his ideas did not always meet with approval from the powers that be and in January 1971 he began his own magazine. Originally titled World Snooker, the following year it became Snooker Scene.

The ethos behind the magazine was to provide a first draft of history by recording every available result. Detailed match reports informed readers as to the ebb and flow of contests, especially valuable in the age before television became heavily involved. Players would also advertise for exhibitions.

In addition, Clive did not stint from providing his analysis of the decisions being made by those charged with running the sport. His intention was that Snooker Scene would incorporate the best parts of Wisden and Private Eye.

Covering a range of sports, including football and rugby, he set up Everton’s News Agency, which supplied reports to newspapers and radio stations. Jim Rosenthal, who later became one of ITV’s best known broadcasters, was an early employee. Clive was a regular hockey reporter and even set up Hockey Scene, a monthly magazine modelled on its snooker equivalent.

Gradually, though, snooker’s popularity was such that Clive poured all of his energies into evangelising for it and billiards.

He took over the running of the British Junior Championship after it had lapsed and played a key role in the founding of the International Billiards and Snooker Federation.

Clive travelled to London in 1968 to interview the squash player, Jonah Barrington, and departed as his manager. Through this venture he got to know Peter West and Patrick Nally, who ran a consultancy specialising in the relatively new world of sports sponsorship. West Nally advised Gallaher, the parent group of Benson and Hedges, and Clive suggested a snooker tournament as a fit for their brand. The B&H Masters was launched in 1975 and has long been regarded as one of the sport’s major events.

Clive won the 1977 National Pairs title with Roger Bales and turned professional at snooker in 1981 but by this time was past his best. He had an exaggerated playing style, twisting himself into each shot following major back surgery. He beat a young John Parrott and former UK champion Patsy Fagan before retiring in 1991.

He fared better at billiards, winning the 1980 Canadian Open, of which he wrote: “In a field of variable quality, I beat Long John Baldrey’s pianist in the first round and Steve Davis in the final.”

Clive reached the quarter-finals of the World Billiards Championship three times and achieved a highest ranking of ninth. He kept a table at home where he would spend many happy hours playing the game he loved.

Clive’s mastery of the English language and encyclopaedic knowledge of snooker made him a natural choice for commentary when the sport established a foothold on television. He auditioned for the BBC in 1963 and was told he had done well but heard nothing more. In the mid-1970s he undertook a commentary test for executives from Thames TV, held at Stoke Poges golf club which housed a snooker table.

The executives enjoyed a boozy lunch – Clive abstained – and repaired to the snooker room to play a frame over which he was expected to commentate. The standard was predictably appalling but Clive passed the audition and was engaged by various ITV regional companies to commentate on events before his life changed on the opening day of the 1978 World Championship. Arriving at the Crucible, he was asked by Nick Hunter, the BBC executive producer, if he would be interested in doing some commentary. Confirming he would, Clive was told his first match would be starting in 20 minutes time.

It was an encounter between Willie Thorne and Eddie Charlton. With typical sardonic humour, Clive described it as a time when “Willie had yet to lose his hair and Eddie had yet to acquire more.”

He quickly became a mainstay of the BBC team, the third lead commentator behind Ted Lowe and Jack Karnehm. After Karnehm retired in 1994 and Lowe in 1996, Clive became widely known as the ‘Voice of Snooker’ and was behind the mic for many memorable moments.

His commentaries were notable for his crisp, spare, pinpoint use of language, with not a word wasted. He only spoke when necessary. When he did, it was worth hearing.

“Warning: genius at work,” was how he once summed up a Jimmy White century.

“Ray Reardon six times world champion in the 70s, Steve Davis six times in the 80s, but it’s a magnificent seven times for Stephen Hendry in the 90s,” he said as Hendry triumphed in 1999.

“Amazing, astonishing, astounding,” was his summation of Shaun Murphy’s shock capture of the 2005 world title.

Clive was aware of the need for journalistic distance in commentary, using surnames when describing the players to avoid any suggestion of bias. He was friendly with players but not one for socialising. You would not see him in the hotel bar at night.

When not in the commentary box he would be found in the media centre, writing daily reports for the Guardian newspaper and updating listeners on BBC Radio 5 Live. At the weekend he wrote first for the Sunday Times and later the Independent on Sunday.

Over the course of his career he wrote close to 30 books about snooker and billiards, whether technical, historical or biographical.

Snooker Scene remained his great passion and an outlet in which he scrutinised the administration of the game, often leading to serious disagreements with the authorities. Clive himself briefly served on the WPBSA board but understood the conflict of interest involved. Instead, he was often a thorn in the side of various chairmen, board members and executives.

As a campaigning journalist, he was at times obsessed with snooker politics as the change he desired time and again failed to materialise. He could suffer depressive episodes and found it almost impossible to switch off from work.

His battles with those in power led to various legal threats but he stood his ground and was eventually delighted by the arrival of Barry Hearn at the WST chairmanship in 2010, ushering in an era of change and growth.

Clive loved absurdist humour. He would not want his own obituary to be entirely serious.

Fortunately, there were lighter moments, most notably at the Grand Prix in Preston in 1998 when he toppled backwards off his chair while in the box. Attempting to halt the inevitable fall, he grabbed the tie of his co-commentator, Dennis Taylor, almost strangling the 1985 world champion.

A cultured man, he once wrote a novel based in the tennis world. Handwritten on several hundred sides of A4, he intended to take the first draft to the office for revisions but, on putting the stack of paper on the roof of his car while he unlocked the door, a gust of wind scattered the pages far and wide and the project was abandoned.

By his own admission, he was hopeless with technology. For many years, he did not own a computer, preferring to hand write his reports and dictate them down the phone to newspaper copytakers. When they were phased out, he was forced to buy a laptop and had to be given several lessons in how to send an email.

Clive made no secret of his disappointment at being phased out of the BBC commentary team but continued on Sky Sports in their coverage of the Premier League and headed the ITV team when they returned to the snooker fold in 2013. He remained there until the Covid pandemic of 2020, when his age meant his was unable to travel to events with their strict protocols.

He was by now in his 80s and diagnosed with Parkinson’s, a condition which took a physical toll and left him unable to write by hand. It forced him to relinquish the editorship of Snooker Scene in 2022 after 51 years at the helm, something he struggled to accept.

However, his interest in the sport did not diminish. He still contributed articles to the magazine and watched tournaments from home, as fascinated by snooker as he was as a youth.

Proudly anti-establishment, his achievements were nevertheless in time recognised by those in authority. He was inducted into the WST Hall of Fame in 2017 and in 2019 was awarded an MBE for his services to the sport. In 2022, The British Open trophy was named in his honour.

These were fitting accolades for someone who had contributed so much to snooker’s own success story. He was respected by colleagues in the media, players and snooker fans as an authoritative figure and huge source of anecdotes spanning the sport’s long history. He had known every world champion since the first, Joe Davis, and his work was a celebration of their collective efforts.

Clive Everton devoted his life to snooker and billiards and was perhaps the greatest friend these sports have ever had.

We have lost something special with his passing but have gained so much more from his many decades of loyal service.