Full History

In 2019, Judd Trump became the first player ever to win in excess of £1m in prize money in a single season. His capture of the World Championship title was watched by hundreds of millions of viewers across the globe, fans of a sport which began as an experiment by British army officers and became a hugely popular television attraction.

Two of snooker’s leading journalists, Hector Nunns and David Hendon, plot snooker’s course from small beginnings to a major international sport…

India, birthplace of snooker

The first ever Indian Open world ranking event was staged in New Delhi in October 2013, an occasion celebrated with gusto throughout the snooker world.

This was partly due to the emergence of two fine professional players from that country, eventual finalist Aditya Mehta and former billiards champion Pankaj Advani, with the prospect of plenty more to follow.

However it also provided the perfect opportunity to reflect upon the very origins of the sport 138 years earlier, with the game having been invented in 1875 by the British Army in the Indian town of Jubbulpore (or Jabalpur, as it is now known) situated around 450 miles south-east of the capital.

India’s Aditya Mehta reached the final of the 2013 Indian Open

According to author and essayist Compton MacKenzie in his account in ‘The Billiard Player’ magazine of 1939, young lieutenant Neville Chamberlain (not the former British Prime Minister) was experimenting on the officers’ mess table with the existing game of ‘Black Pool’ featuring 15 red balls and a black.

Having thrown on additional coloured balls and heard that rookie cadets at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich were called ‘snookers’, Chamberlain observed that all those present were snookers at this tweaked version of the game, and the name instantly stuck.

His Devonshire regiment, which later became the Devonshire and Dorset and are now known as the Rifles, remain fiercely proud to this day of their role in the invention of snooker.

Soon after, Chamberlain was based in the Tamil Nadu hill station of Ootacamund – or ‘Snooty Ooty’, as the exclusive mountain retreat was often known. And such was the young officer’s enthusiasm for his new game there that he even named his horse ‘Snooker’.

The further development of the sport took place in the colonial-style Ooty Club, very much a part of snooker folklore and somewhere that current World Snooker chairman Barry Hearn insists remains on his ‘bucket list’ to visit.

The club features an original snooker table from the period in use today and walls still thick with tiger, leopard and deer hunting trophies – and it was from here that word and rules of the new game circulated throughout India and the former British Empire.

Membership of the club at that time was restricted to “officers of the armed forces, and gentlemen moving in general society”, though luckily for most, those rules have since been eased.

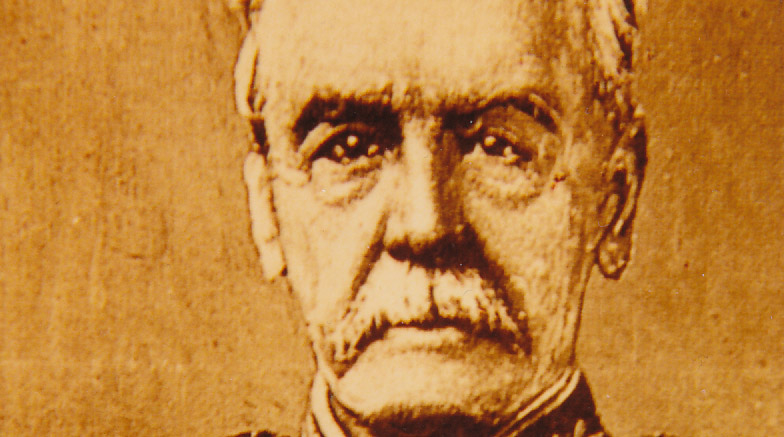

Lieutenant Neville Chamberlain is credited with the invention of snooker

Rumours of this new phenomenon had reached Great Britain and aside from the birth of a certain Joe Davis in 1901 – more of whom later – the years that followed saw snooker slowly grow in the United Kingdom, cue manufacturer and billiards player John Roberts Jr helping to spread the gospel after a trip to India.

Around 1910, century breaks were attributed to Scot Tom Aiken, a billiards champion, Cecil Harverson, Phil Morris of Tottenham and Lucania Hall manager George Hargest.

The first amateur snooker championship was staged during the Great War, with the result at that time decided by points aggregate after seven frames – a very early precursor to the shorter format of the modern-day European and Asian Tour series.

Snooker’s rules, which had featured inconsistencies, were finally dragged together in 1919, also the year that the re-spotted black was introduced to ensure each frame had a winner. How much drama that innovation has produced over the years, and still does to this day.

With a number of established amateurs, it took a man who would become snooker’s first superstar to usher in the age of professionalism.

Joe Davis and professionalism

Snooker’s next era belonged to one man only – the incomparable and all-conquering Joe Davis. The others involved as professionalism took a hold were more often than not bit-parts in the Joe show and they knew it, with varying levels of resentment.

However the years from the mid-1920s unquestionably also marked an exciting phase in the game’s emergence and saw it challenge and overtake the more established game of billiards in the UK, with matches drawing crowds in the thousands.

Joe, along with younger brother Fred, was born in Whitwell, Derbyshire just past the turn of the century – sons of a miner who turned publican at the Queens Hotel, Whittington Moor which crucially housed a full-size billiards table.

And Joe would go on to become a strong contender for the tag of greatest player of all time with his incredible longevity at the top and unmatched exploits on the table. He won 15 world titles in succession, the last coming after World War Two.

He was also the driving force behind the first professional World Championship in 1927, the forerunner of today’s tournament that will be watched by hundreds of millions around the globe. The famous silver trophy that will be held aloft by this year’s champion on May 5 has not changed – bar a few extra names engraved in the intervening years.

Joe and Fred Davis, pictured with their mother

Though weaned on billiards and like many others initially looking down on the new sport Joe, a financial pragmatist, immediately saw snooker’s greater earning potential.

When he claimed victory from a field of 10 entrants in that 1927 final at Camkin’s Hall, Birmingham, 20-11 against Tom Dennis, the man unable to focus with his right eye and variously called the ‘Sultan of Snooker’ and the ‘Emperor of Pot’ pocketed a princely £6 10s.

Sidney Smith, another son of the Derbyshire snooker hotbed of the time, became the first man to make a total clearance (136) at the Daily Mail Gold Cup in 1939.

And the first post-WWII World Championship final between Joe and Australian Horace Lindrum, won 78-67 by the Englishman at the Royal Horticultural Hall to sell-out crowds of 1,200 twice a day for a fortnight, represented a peak leading to almost inevitable decline in interest and commercial sway.

Fred won the first of his eight world titles in 1948, and the BBC, who are again providing the pictures from this year’s Crucible action, made their debut outside broadcast coverage of snooker from Leicester Square Hall in 1950.

In 1952 a boycott by most of the top players left only two entrants. Lindrum beat New Zealander Clark McConachy 94-49 at Houldsworth Hall in Manchester in a ‘world final’ contest recognised by virtually nobody, though Lindrum’s family were still protesting he was the first Australian to win it when Neil Robertson lifted the trophy in 2010.

The great Joe Davis

And on January 22 1955 Joe, also referred to as the ‘Grandfather of Snooker’, became the first man to have a 147 maximum break officially recognised in an exhibition against Willie Smith that effectively also brought the curtain down on Leicester Square Hall, formerly Thurston’s (a table manufacturer) and an iconic playing venue for half a century.

Joe, having already produced at least two coaching manuals, brought out in 1956 the definitive ‘How I Play Snooker’, a sacred text of technical know-how that has since been described as “the bible” for all players by six-time world champion and namesake Steve Davis, handed the book by his father Bill. One of the 56-year-old’s only unfulfilled career ambitions remains to bring out a tome to rival it.

However, Joe’s decision to retire from the World Championship in 1946 but continue to play in tournaments and exhibitions seriously devalued the game’s premier event as everyone knew the best player wasn’t in it. It led to a decade of decline before the sport was rescued by a medium which would herald a new dawn.

The age of colour

In July 1969, man first walked on the moon and, that same month, snooker took its own giant leap, which would lay the groundwork for the professional circuit as we know it today.

Pot Black was a weekly series designed to showcase the BBC’s new colour service. The controller of BBC2 was David Attenborough, who would become a broadcasting legend through his ground-breaking natural history programmes. He wanted content which could emphasise colour. Snooker, which also had the advantage of being easy to cover, fitted the bill perfectly.

The leading lights

Ted Lowe, a former manager of Leicester Square Hall in London, who had lent whispering commentaries to snooker shown by the BBC in black and white, devised the format and eight professionals were invited to play. The series was a huge hit and players quickly became well known, which in turn boosted their capacity to earn money from exhibitions.

All this had seemed unlikely in 1957 when snooker’s very future appeared doomed when the World Championship was discontinued through lack of interest. It had been revived by Rex Williams in 1964 and played as a series of challenge matches, all seven of which were won by John Pulman. In 1968, the World Professional Billiards and Snooker Association was established and the following year the championship reverted back to a knockout format. John Spencer won it in 1969 but Ray Reardon, a former miner and policeman, would dominate the 1970s, winning six world titles.

Reardon was the period’s leading player but its star was a young Northern Irishman whose lightning fast skills had been honed in the Jampot club in Belfast. Alex Higgins was a firebrand whose very being seemed destined to challenge the establishment on and off the table. He won the world title at his first attempt in 1972, pocketing a first prize of £480, and spectators packed into exhibitions to watch him play.

It was ‘Hurricane’ Higgins, despite his bad behaviour, or maybe because of it, who gained snooker popularity and publicity in this time where Pot Black was still the sport’s main TV outlet. Sponsors, particularly from the tobacco industry, started to take notice and the BBC increased its coverage with highlights from the World Championship and a new invitation event, the Masters.

Alex Higgins would win two world titles

As Reardon, Spencer and Higgins led the way on the table, things were moving forward behind the scenes under the astute stewardship of Mike Watterson, an independent promoter who was savvy enough to realise the sport’s potential as television exposure created increased sponsorship opportunities.

The World Championship had been played in various outposts, including Australia, before Watterson looked for a new home for the 1977 tournament, ideally an intimate set-up which could become a permanent venue for the sport’s Blue Riband event. One night his wife, Carol, returned from seeing a play at a theatre in Sheffield which she thought may fit the bill.

And so the stage was set for snooker’s transformation from relative obscurity to front page news as the game hit the heights like never before.

Davis at the head of the snooker boom

The Crucible stands in the middle of Sheffield city centre. For 50 weeks of the year this theatre-in-the-round stages great dramatic works, but for 17 days annually it becomes a sporting hub where careers are defined and dreams are made or shattered.

John Spencer triumphed at the 1977 championship there before Ray Reardon won his sixth world title the following year. 1978 had seen the BBC considerably increase its coverage of the tournament and they were rewarded with stellar viewing figures. In a decade, only Alex Higgins had successfully challenged the Reardon/Spencer grip on the World Championship but the old order was to be irrevocably broken in 1979.

Terry Griffiths’s triumph as a qualifier in his first season as a professional acted as a catalyst for many amateurs to take a chance on the pro ranks. One ginger-haired Londoner had already made the leap. Steve Davis of Plumstead was a shy but dedicated player tutored by his father, Bill, and managed by an extrovert businessman called Barry Hearn, who ran a chain of Lucania snooker clubs.

Steve Davis – king of the 80s

As the 1980s dawned, Davis and Hearn set about cleaning up on and off the table. Davis’s first major success came at the 1980 UK Championship and he ended the season by winning the world title, Hearn barrelling across the Crucible stage and nearly knocking him over in jubilant celebration. With the world champion under his wing, Hearn began to see the possibilities of snooker outside of mere results. With a natural touch for the popular he began to build his Matchroom empire by signing more players and promoting independent tournaments.

These were golden years. All over the UK, snooker clubs were opening and a vibrant amateur scene began breeding the stars of the future. ITV had enviously viewed the BBC’s audience figures and began televising its own events. Thus, a professional circuit built up and prize money rocketed. Sponsors were lining up to invest in a sport which the British public watched like a soap opera, with its distinct cast of characters, many of whom found their private lives the subject of unwanted attention from a tabloid press also riding the boom.

Higgins was inevitably the subject of many of these stories. The volatile bad boy of the baize won an emotional second world title in 1982, tearfully beckoning his wife and baby daughter on to the Crucible stage in the moments following his 18-15 victory over Reardon.

Cliff Thorburn had become the first non-British world champion in 1980 and made the Crucible’s first 147 break in 1983, a year before another Canadian, Kirk Stevens, made one at the Masters.

Jimmy White, who had won the world amateur title at the age of 18, missed out on a world final place in 1982 when Higgins made a miraculous clearance of 69 while trailing 15-14 in their semi-final before winning the decider. White fought back from 12-4 down to Davis in the 1984 final but was beaten 18-16.

Dennis Taylor won snooker’s most famous match

Davis was indeed the man to beat. He made the first televised maximum break at the 1982 Lada Classic, captured six UK Championship crowns and spent seven years as world number one. However, he was on the wrong end of the most famous snooker match of the boom years. In 1985, he built an 8-0 lead over Dennis Taylor in the world final and was apparently coasting to a third straight title. Taylor, a Northern Irishman who wore large ‘upside down’ spectacles, fought back and at 11pm they were level at 17-17 with one more frame to play.

It lasted over an hour and came down to the final black. Davis had a chance to pot it but missed, leaving Taylor to sink it. 18.5 million viewers were still watching BBC2, a record audience to this day for the channel and for any UK programme broadcast after midnight.

Despite this reverse, and one to 150-1 pre-tournament hopeful Joe Johnson in 1986, Davis, like snooker itself, remained imperious throughout the 1980s. In 1989, he crushed John Parrott 18-3 to win a sixth world title.

He seemed unstoppable, but a young man from Scotland had other ideas.

The Hendry years

Every so often in sport there comes along an individual who not only dominates rivals in competition, but introduces a whole new dimension and changes the way a game is played – and Scotland’s Stephen Hendry was to prove just such a figure in snooker.

Born in South Queensferry, Hendry was bought a small table by his parents as an afterthought at the age of 12. On such twists of fate are legends formed. He swiftly served notice of a growing force with wins at the Scottish Under-16 and Scottish amateur level, turning professional at the tender age of just 16 years and three months.

By the time Hendry retired in 2012, he had set records that may never be broken, and built up a glittering and trophy-laden CV, not least with his achievements on the greatest stage of all, the World Championship at the Crucible Theatre.

Hendry’s legacy will therefore not only be title triumphs and memories, but the certainty that many of those now at the top of the game were hugely influenced by what they saw him doing on the table in his pomp, the shots he played and the attacking approach to break-building and single-visit snooker he espoused.

With the world waiting for someone to inherit the Steve Davis mantle, Hendry – with manager Ian Doyle guiding his career – unhesitatingly leapt up to the plate.

Stephen Hendry – seven times a world champion

The early milestones came and went. There was a first Crucible appearance at 17, famously being applauded off by Willie Thorne after losing 10-8. And a first ranking title in 1987, as Hendry beat Dennis Taylor 10-7 at the Grand Prix.

The dominance truly began in the 1989-90 season, culminating in a first world title – and Hendry remains at the time of writing the youngest player to win it at 21 years 106 days. Six further times Hendry lifted the trophy at the Crucible, and inevitably his series of finals against People’s Champion Jimmy White are the best remembered, with the Scot often unfairly cast in the role of the hunter who killed Bambi’s mother.

Four times he snatched the prize away from the Whirlwind, including the remarkable ten frames in a row to win 18-14 in 1992, and the ice-cool 58 clearance to win 18-17 in 1994 with a broken bone in his arm after White had missed a black off the spot in the decider.

In these and other successes Hendry was fearless, aggressive, ruthless, focused and determined – and executed tough shots under the most intense pressure time and time again. And he never forgot the trailblazing he was doing for Scottish snooker, walked in by a piper with Alan McManus for their all-Tartan 1993 Crucible semi-final.

Not all of Hendry’s finest moments came in Sheffield, though. In 1994 he made seven century breaks in the UK Championship final, beating Ken Doherty 10-5 in Preston. And in 1997 he recovered from losing six frames in a row in the final of the Liverpool Victoria Charity Challenge to come out at 8-8 and win the match against Ronnie O’Sullivan with a 147 maximum break.

Jimmy White – played Hendry in four world finals

Victories over Hendry in big matches at or near his peak were rare, hard-earned and for that reason all the more special. Just ask Ken Doherty what beating him in the Crucible final meant in 1997, or Peter Ebdon with his ‘revenge’ showpiece victory in 2002 after losing in the 1996 final. John Parrott and John Higgins also claimed world titles in the 1990s.

Hendry also remains the last snooker player to seriously figure in the annual BBC Sports Personality of the Year poll, coming second only to Paul Gascoigne in 1990. For many, Hendry gets the nod as the greatest player of all time – but like all reigns his was to end, with a group of players he inspired seizing the initiative.

The golden crop bear fruit

While Stephen Hendry was taking snooker to another level in the early 1990s, a trio of teenagers were taking their first steps on the professional circuit, the start of a journey which would propel all three to the top of the sport.

The circuit had gradually grown from a handful of professionals to 128 players, but in 1991 the WPBSA decided to throw the pro ranks open to anyone willing to pay the entry fees. Suddenly there were 700 professionals, a revolution which swept away many of the now ageing characters who were such an important part of the 1980s boom.

Ronnie O’Sullivan’s name was known long before he turned professional. His father, Ronnie senior, instilled in him a disciplined practice routine from boyhood and brought leading amateurs to the family home to play his son on their full sized table. O’Sullivan cut a swathe through the amateur ranks and won 74 of his 76 qualifying matches in his debut season, 1992/93.

Snooker had decamped to the Norbreck Castle Hotel in Blackpool for a long summer of preliminary rounds and O’Sullivan emerged as the undoubted star. Remarkably, a year later he beat Hendry 10-6 in the UK Championship final the week before he turned 18, becoming the youngest ever ranking event winner. His performances were often dazzling. At the 1997 World Championship he made a 147 break in a record time of just five minutes, 20 seconds.

Ronnie O’Sullivan – leading the class of ’92

O’Sullivan had the world at his feet. But away from the table, he struggled from depression, triggered by his father’s life conviction for murder. O’Sullivan’s magisterial performances on the baize were therefore coupled with erratic behaviour, disciplinary action and constant threats to retire.

He did not win his first world title until he was 25, in 2001. A second followed in 2004 and third in 2008. After his fourth in 2012 he finally went through with his threat to walk away, taking a year off, apart from one minor event. However, the time away proved to O’Sullivan that snooker was still in his blood. He returned to win a fifth world title in 2013. With five UK and six Masters titles, plus a record 13 maximum breaks, his claim to be the greatest ever was strengthened in his late 30s, when most players decline.

He could have won more but for his two contemporaries, John Higgins and Mark Williams, the other celebrated members of the class of 1992.

Higgins, an all-round player in the Steve Davis mould, was the first of the three to win the world title. His 1998 triumph saw him end fellow Scot Hendry’s eight-year reign as world number one.

Higgins, who had won three ranking titles while still a teenager, was a regular tournament winner but it took him nine years to capture a second world title. He quickly won two more, in 2009 and 2011, as well as three UK titles and the Masters twice.

Mark Williams – snooker’s first left-handed world champion

Williams became the third Welshman and first left-hander to win the World Championship in 2000. In 2003, he won a thrilling contest with Ken Doherty 18-16 to complete a clean sweep of that season’s three major titles, having already captured a second UK Championship and second Masters, a feat only previously accomplished by Davis and Hendry. And Williams proved just how great a player he was by winning a third world title in 2018, 15 years after his second, following a remarkable resurgence in form during that season.

Laid back off the table, Williams was ruthless on it, his mettle having been proven by edging Hendry 10-9 on a re-spotted black in the 1998 Masters final.

O’Sullivan, Higgins and Williams were products of the 1980s UK snooker boom. They were inspired by the blanket TV coverage, played in the sundry junior and amateur events and climbed their way up from the bottom rung of the qualifying ladder to the very top. From 1998 to 2013 they won 11 of the 16 World Championships between them.

They were the leading lights as snooker entered a new millennium, which would see the sport exploring new global opportunities.

Snooker goes global

Despite its British roots, professional snooker made several forays to foreign climes before travelling became the norm for top players.

South Africa staged challenge matches in the 1960s, the 1975 World Championship was played in Australia, there were regular tournaments in Canada in the 1970s and in the 1980s Barry Hearn’s Matchroom led the way in spreading the gospel to countries such as China, Hong Kong, Thailand and the United Arab Emirates.

The first ranking event staged outside the UK was the 1988 Canadian Masters. There were European Opens in France, the Netherlands and Belgium and an Asian Open in China in 1990. Thailand became a regular and popular stopping off point for the circuit in the 1990s after the emergence of James Wattana, who won three ranking titles, including his home event on two occasions.

It was not until the new millennium however that snooker’s global reach was truly explored thanks to a Chinese teenager and a pan European broadcaster.

Ding Junhui had been touted as a star of the future from a very young age but found the UK-based qualifying set-up tough. He was withdrawn from the 2005 China Open in Beijing and then re-entered as a wildcard. Sensationally, just days after turning 18, he won the tournament, beating Stephen Hendry 9-5 in the final. 110 million viewers watched on Chinese television and it sparked a boom similar to the one the UK had enjoyed two decades earlier.

Ding Junhui – winner of a historic China Open title in 2005

Meanwhile, Eurosport, which had showed snooker sporadically for years, signed a deal to broadcast every major event, bringing the sport to viewers in 61 countries, many of them completely new to the game.

Like British audiences, they had a cast of characters to which to warm. O’Sullivan, Higgins and Williams remained the holy trinity but there were world titles too for Peter Ebdon (2002), Shaun Murphy as a qualifier (2005) and Graeme Dott (2006). Ding won two UK titles and Neil Robertson of Australia emerged as a top player, eventually triumphing at the Crucible in 2010.

At the Masters, Paul Hunter won three dramatic finals, all in deciding frame finishes having been behind each time. Hunter’s easy going manner, good looks and genuine humility made him a popular new star and his performances helped keep snooker in the spotlight. Everyone in the sport was devastated when he died from a rare form of cancer in 2006 at the age of only 27.

Off table things were less rosy. The UK government had prohibited tobacco companies from sponsoring sport, which helped create a huge hole in snooker’s finances and, despite the increasing global interest, the circuit began to shrink.

There was nothing wrong with snooker on the table but its administration needed a serious overhaul to maximise its popularity. The task fell to a man synonymous with the game’s boom years of the 1980s.

The Hearn Revolution

Today snooker stands as a truly global sport, its tentacles forever reaching into new territories.

It is played in approximately 110 countries by over 120 million people, and watched by around 500 million worldwide. One of the fastest-growing sports on the planet is also knocking on the door for future inclusion in the Olympic Games.

But just a few short years ago the game stood at a major crossroads, having seen the number of full ranking tournaments drop to six, and with leading professionals voicing concerns that their lack of earning opportunities were rendering them little more than ‘part-timers’.

Ronnie O’Sullivan, speaking in 2009 as the situation came to a head, called for a ‘Simon Cowell’ figure to step in and save snooker. As it turned out, that man was Barry Hearn.

Barry Hearn – World Snooker Tour Chairman

Former WPBSA and World Snooker chairman Sir Rodney Walker effectively held a vote of confidence in his own regime in December of 2009, and the membership voted 32-24 against his re-election, paving the way for Hearn to assume control.

And having been voted on as WPBSA chairman Hearn, determined to succeed in a sport that had kick-started his own career, asked for a mandate from the players to take the commercial rights and move it forward.

Owner of Leyton Orient Football Club, a successful darts and boxing promoter and manager of Steve Davis and formerly a large stable of snooker stars at Matchroom in the 1980s, Hearn pledged in a series of frank exchanges with the players, many of them highly sceptical, to put on more events and increase prize money and earning opportunities.

In the build-up to the crucial vote in the summer of 2010, venues were awash with plotters and propagandists whispering in hushed tones, the atmosphere resembling the corridors of power at Westminster at leadership election time.

There is plenty of hearsay evidence of players changing their minds several times while in the car on the way to Sheffield – but in the end potential rival John Davison, a former Olympic shooter, opted not to appear at the Extraordinary General Meeting.

Hearn squeaked home by 35 votes to 29. The revolution might easily not have happened, with the new World Snooker supremo insisting he would have walked away had he lost.

Breaking records – the World Snooker Tour

And he has delivered what was promised in a way that has seen even previously outspoken opponents among the players admit they were wrong, making the regular Players Tour Championship series in Europe and Asia an important part of the calendar.

As prize money rocketed from £3.5m in 2009/10 to nearly £15m ten years later, standards rose on the table. In 2014, Neil Robertson became the first player to make 100 centuries in a single season. Five years later, Ronnie O’Sullivan made the 1,000th century of his career amid extraordinary scenes at the Players Championship final in Preston.

Mark Selby, who broke through as world champion in 2014, occupied the world no.1 position unbroken from 2015 to 2019 before Judd Trump threatened a new era of domination, winning a record six ranking titles during the 2019/20 season.

Mark Selby – Four-time World Champion

The WPBSA have also played a more active role in promoting snooker for all, overseeing a women’s tour and circuit for players with disabilities, as well as supporting a seniors tour.

There have been new tournaments put on in Austria, Germany, China, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Poland, Bulgaria, the Netherlands, Portugal, Gibraltar, Australia, Brazil, Latvia, Thailand and India.

The years have not been without controversy, with some leading players resistant to the removal of protection previously afforded to the top 16, not least coming in at the 128-man stage rather than the last-32 round – but Hearn and WPBSA Chairman Jason Ferguson have never wavered in their view that this is how a democratic and properly run sport should operate, along the golf and tennis models.

Many within the sport expect India to be the ‘new China’, but if one thing is certain it is that India – where snooker was born in the 19th Century, will not be the last new stop on the global route planner as a game which began so humbly continues to fascinate hundreds of millions around the world.