History of the Masters

This season’s Masters is the 47th staging of snooker’s leading invitation event and, given the peculiar times, will be unlike any other. Sadly, crowds cannot be accommodated this year because of the coronavirus restrictions but with a high quality field, the 2021 event can still add greatly to an already bulging store of golden memories created over five decades.

An infant sport in the era of black and white television, snooker crawled like a toddler towards some kind of profile but its early TV appearances were sporadic and exhibition frames during BBC’s Grandstand had little meaning.

Snooker learned to walk and eventually grew into adulthood because of Pot Black, a series which helped showcase the new colour TV service in 1969, suddenly bringing the game into millions of households, making stars of the professionals of the time and paving the way for the professional circuit as we know it.

Through Pot Black and the emergence of genuine stars, most notably Alex Higgins, snooker began to gain a foothold in the popular consciousness. One man who sensed where the growing interest might lead would in time go on to commentate on many of the sport’s most celebrated moments.

In the early 1970s, Clive Everton was a keen amateur snooker and billiards player mainly making a living from journalism. He also managed Jonah Barrington, the leading British squash player of the day.

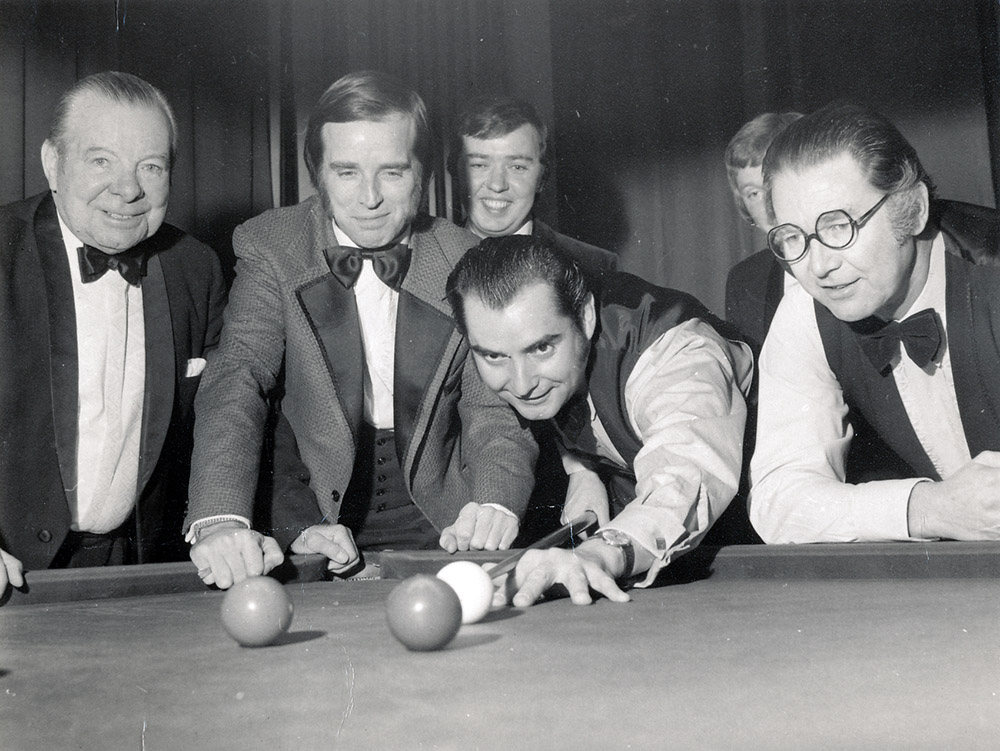

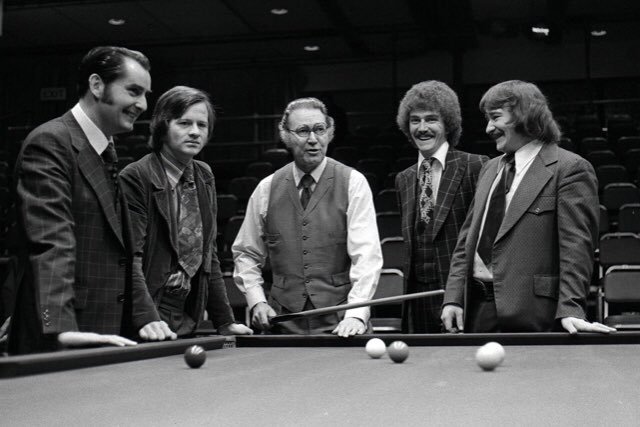

One afternoon, Everton went to a meeting with Peter West and Patrick Nally, who ran a promotions company, seeking sponsorship for Barrington. The meeting went well and they confided they were pitching to promote the Gallaher tobacco brands – which included Benson and Hedges – through sporting events. Did Clive have any ideas? Thankfully, he did and the Masters was born in 1975.

It was initially for just ten invited players, staged at the West Centre Hotel in London. The two pre-eminent champions of the 1970s, John Spencer and Ray Reardon, reached the final, which turned into a thriller.

At 8-8, Reardon looked set to win the decider but was put off by the presentation party preparing to make their way to the arena floor and Spencer eventually scrambled home on a re-spotted black to win the £2,000 first prize.

Professional snooker was yet to become the slick operation of today and there were many teething problems. In Snooker Scene, Everton headlined his retrospective on the event ‘Two Cheers for Benson and Hedges.’

Blanket BBC coverage was some time off, but the event continued the following year at the New London Theatre and moved to Wembley Conference Centre in 1979.

This was the year South African Perrie Mans won the title with a highest break of 48, the first ever Masters centuries having been made in the quarter-finals by Doug Mountjoy and Higgins.

In 1981, the field expended to 12 players and in 1983 to the world’s top 16. By now, snooker was riding the crest of a wave on British television and the Masters became another popular event with viewers, although its ‘triple crown’ status had not yet been bestowed and its first prize lagged behind many of the circuit’s other big TV events. The BBC did not cover every day until 1984.

However, its prestige grew and grew. The Masters was only ever intended for the crème de la crème. And it always felt different for the players because it was promoted independently of the WPBSA and, with B&H having plenty of money to spend, the hospitality was considerable.

Thus, the players felt special and so the event felt special. Its cache came from its elitism. This was a tournament for the sport’s very best exponents played in the nation’s capital. And it was clear from early on that the often raucous London crowd played a major part in its appeal.

This was never more evident than when Alex Higgins, a twice champion, was playing. His fans were so passionate that they were known to storm on to the arena floor in the aftermath of his victories, such as in 1985 when he beat Steve Davis in the first round.

The previous year had seen two exciting young crowd pleasers serve up a memorable semi-final.

Before Judd Trump and Jack Lisowski there was Jimmy White and Kirk Stevens. Amid a barrage of potting there were three centuries, the most celebrated being Stevens’s dashing 147, only the third official maximum break ever recorded. It was such a special moment that a representative of the sponsors came into the arena to make a speech between frames before the match resumed. White would prevail and went on to win the title.

In 1986, Cliff Thorburn became the first player to win the Masters three times, a feat which would be eclipsed in style by Stephen Hendry, who made his debut in 1989 and promptly won the title five years running.

This extraordinary spell of dominance, which led to Hendry being given the trophy to keep, included his recovery from 8-2 down to Mike Hallett in 1991. Hallett – whitewashed 9-0 by Steve Davis in the final three years earlier – had missed the pink to win 9-2.

Hendry’s great run was finally ended by Alan McManus in a deciding frame finish to the 1994 Masters. The following year, two teenagers provided a glimpse of snooker’s future by reaching the final. Ronnie O’Sullivan beat John Higgins 9-3 to become, at 19, the youngest ever winner of the title. It is remarkable to consider that if O’Sullivan can win the title this year he will, at 45, become its oldest ever champion.

It said something about Davis’s imperious command of the snooker world in the 1980s that his return of two Masters titles in this decade was seen as underachievement. He never quite clicked at the tournament, possibly because despite being a Londoner on home soil, he suffered booing and abuse from a crowd happy to see anyone but him triumph.

By 1997 and now thought, at 39, to be in decline, the tide had turned. Now, Davis was a much-loved elder statesman and, despite a distinct lack of form, he authored one of the great Masters stories by rallying from 8-4 down to O’Sullivan to win their final 10-8 (with increased BBC transmission hours, from 1996 matches were now extended to best of 11s with the final best of 19).

That 1997 final was also notable for the appearance of a streaker, Lianne Crofts. No stranger to exhibitionism, she had once taken part in a naked bungee jump.

In 1998, 23 years after Spencer had edged Reardon on the extra ball, the Masters once again came down to a re-spotted black finish. Mark Williams had trailed Hendry 9-6 but forced the decider and sank the re-spot after Hendry had missed a chance to left middle.

By now the Masters had become one of snooker’s premier events, eagerly targeted by the game’s leading lights. In 1999, John Higgins, having already won the World and UK titles for the first time the previous year, and perhaps influenced by the unfolding Five Nations rugby union event, told the press ahead of the final, “that triple crown would be a dream.”

To win the title Higgins beat Ken Doherty, who a year later missed the last black of what would have been a 147 in the final against Matthew Stevens, costing him a sports car worth around £80,000.

In 2003, B&H were forced to withdraw their association with the Masters because of government legislation prohibiting tobacco sponsorship of sporting events. World Snooker took it over and, to the casual viewer, not much changed except the set.

This was a time of transition for snooker, of civil wars and political strife. That the sport could survive intact was in large part down to the players who continued to enthral and entertain.

Chief among them in this period was Paul Hunter, a laidback lad from Leeds with a fierce talent. Handsome and with a relatable personality, he had won the Welsh Open in 1998 at the age of 19 but achieved national prominence through his capture of the Masters in 2001.

At the halfway stage of the final, Hunter trailed Fergal O’Brien 6-2. In the evening, he roared back with four centuries to win 10-9. Afterwards he made an innocent remark that he had gone back to the hotel between sessions with his girlfriend, Lyndsey, and ‘put plan B into operation.’ This throwaway comment landed him on the front pages and a star was born.

The Masters was the tournament for which Hunter is most remembered. The following year he came from 5-0 down to beat Mark Williams 10-9. In 2004, he completed a hat-trick of comebacks from unlikely positions by recovering from 7-2 behind to edge O’Sullivan 10-9, making five centuries in the match.

It took longer than it should have done following Hunter’s sad death in 2006 to name the Masters trophy in his honour, but he is now rightly celebrated each year.

In 2006, the Wembley Conference Centre hosted its last Masters. This fine venue was being bulldozed as part of the stadium redevelopment. Sad though this was, it received the best possible send off with a third meeting in the final between Higgins and O’Sullivan.

O’Sullivan had comfortably prevailed in the each of the first two but this time it was Higgins who took the spoils in a roof-raising ending, courtesy of one of the best pressure clearances ever seen.

O’Sullivan was in first in the decider with 60 but missed a slight cut-back red to the yellow pocket, a few balls from the title. After a short safety duel, Higgins attempted a red to the right middle. No one was sure at first if he had hit it hard enough. It hung agonisingly on the lip before finally dropping. Cool in the eye of the storm, Higgins completed a 64 clearance to secure victory.

This year, Higgins sets a new record with his 27th successive appearance in the event. Davis and White also appeared 27 times but not consecutively.

The 2006 defeat was a temporary setback for O’Sullivan, who would go on to become the record breaker at the Masters with seven titles to his name thus far, one more than Hendry. He has also made 73 centuries in the event – 28 more than Hendry in second place – and won more matches than anyone else.

In 2007, he won the first Masters staged at its new home, the rather cavernous Wembley Arena, beating Ding Junhui 10-3 in what proved to be a brutal experience for the still teenage Chinese superstar, who had opened the event in happier fashion with a 147.

The Masters was still at Wembley but the Arena never quite recaptured the atmosphere of the Conference Centre. Ding won the last staging there in 2011 before the tournament moved to Alexandra Palace, an iconic and imposing building offering stunning views of the London skyline.

Neil Robertson was the first champion at Ally Pally, followed by triumphs for other modern greats such as Shaun Murphy and Judd Trump.

It was also the scene for Mark Selby’s third Masters success in 2013. Like Hendry, Selby had triumphed on his debut in 2008, winning three deciders to reach the final. In 2010, he underlined his growing reputation as the master of brinkmanship by coming from 9-6 down to edge O’Sullivan 10-9.

The Masters provided Mark Allen with his biggest career success to date in 2018 and last year Stuart Bingham added to his trophy haul, waiting for the very last frame of the final to make his first century.

The scenes of jubilation which followed Bingham’s victory, together with impressive new hospitality areas adding to the event’s prestige, seem longer than a year in the past. Snooker has had to stage events behind closed doors for several months due to the Covid pandemic.

It isn’t the same without fans but we have seen in recent months that snooker at the highest level can continue to provide drama and excitement even in much changed circumstances, thanks to the quality of play produced by the players and the continued hard work of the World Snooker Tour team.

This will surely remain the case at the Masters, one of snooker’s truly special events.

With just one table, every match feels like a final. The change in the ranking system under Barry Hearn’s stewardship of World Snooker means that the current top 16 is a more accurate reflection of the sport’s elite than in the days when a player’s ranking position was set for the whole season.

These are difficult times, but the Masters can provide a real winter warmer as snooker’s best of the best prepare to once again put on a show worthy of this great tournament’s history.

Article by David Hendon.